23.09.2021

Games of the Future

Virtual and augmented reality

It's not that hard to lift the veil of the future if you just look around carefully. The iPhone or any smartphone is a development of technology that already existed in the form of early versions of the telephone, which in turn emerged from the landline. Tron, The Lawnmower Man, The Thirteenth Floor, The Matrix, or Steven Spielberg's Ready Player One although they are a peculiar and somewhere naive interpretation of virtual reality, they represent quite clearly what will already be possible in our century.

The left side of the illustration is a poster for Ready Player One, while the right is a shot from Andrey Gubin's music video "Winter frost," shot in the second half of the 90s.

Full "immersion" in virtual reality has been discussed in popular culture almost since the first games but, some ideas can be traced even before their emergence - in 1964, Stanisław Lem in his book Summa Technologiae (the title is in Latin, meaning "Summa (Compendium) of Technology" in English) under the term "Phantomology" describes the problem and the essence of the answer to the question "how do we create realities for the intelligent beings that exist in them, realities that are absolutely indistinguishable from the standard reality but that are subject to different laws?" An even earlier description of virtual reality can be found in the story Pygmalion's Spectacles by the American science fiction writer Stanley Weinbaum, published in 1935, which described a device that was put on the user's head, filled with a special liquid and allowed to plunge into a world of illusion.

...

"The liquid before Dan's eyes clouded suddenly white, and formless sounds buzzed. He moved to tear the device from his head, but emerging forms in the mistiness caught his interest. Giant things were writhing there.

The scene steadied; the whiteness was dissipating like mist in summer. Unbelieving, still gripping the arms of that unseen chair, he was staring at a forest. But what a forest! Incredible, unearthly, beautiful! Smooth boles ascended inconceivably toward a brightening sky, trees bizarre as the forests of the Carboniferous age. Infinitely overhead swayed misty fronds, and the verdure showed brown and green in the heights. And there were birds—at least, curiously lovely pipings and twitterings were all about him though he saw no creatures—thin elfin whistlings like fairy bugles sounded softly."

The scene steadied; the whiteness was dissipating like mist in summer. Unbelieving, still gripping the arms of that unseen chair, he was staring at a forest. But what a forest! Incredible, unearthly, beautiful! Smooth boles ascended inconceivably toward a brightening sky, trees bizarre as the forests of the Carboniferous age. Infinitely overhead swayed misty fronds, and the verdure showed brown and green in the heights. And there were birds—at least, curiously lovely pipings and twitterings were all about him though he saw no creatures—thin elfin whistlings like fairy bugles sounded softly."

Nowadays, in Russia (as well as outside of it) there's a whole series of LitRPG books about "popadanstvo" (accidental travel) or the same world-popular anime Sword Art Online, in which the characters get stuck and fight in a virtual world in an attempt to get out back to the real one. Moreover, attempts to approach this technology start far from the Oculus Rift or Google Cardboard goggles, a funny cardboard version based on a gyroscope and an ordinary smartphone screen.

Link Trainer

Attempts to create a simulation of reality began much earlier than Lem and Weinbaum's ideas. One of the first such attempts was a variation of physicist Sir Charles Wheatstone's stereoscope, which appeared in 1838. This device can be called the forerunner of today's 3D glasses and virtual reality. Wheatstone invented a binocular optical device for viewing three-dimensional images, in which mirrors were used at a 45° angle to display side pictures. In this way, the brain combined a photograph of a single object into a single three-dimensional image, but it still did not involve the physical sensation of what was seen. Inventor Edwin Link was able to come close to this type of simulation when he created the first commercial flight simulator in 1929. His "Link Trainer" simulated the flight of a real airplane and was a wooden fuselage with a cockpit. The simulator stood on a pneumatic moving platform on inflatable cushions and was equipped with a special mechanism that pumped in and out air - this system made it possible to simulate pitch, roll, yaw, lift, sway, and tilt. The U.S. Air Force was interested in Link's technology, and during World War II, more than 10,000 such simulators were used for safe training and reducing its time while training more than 500,000 pilots.

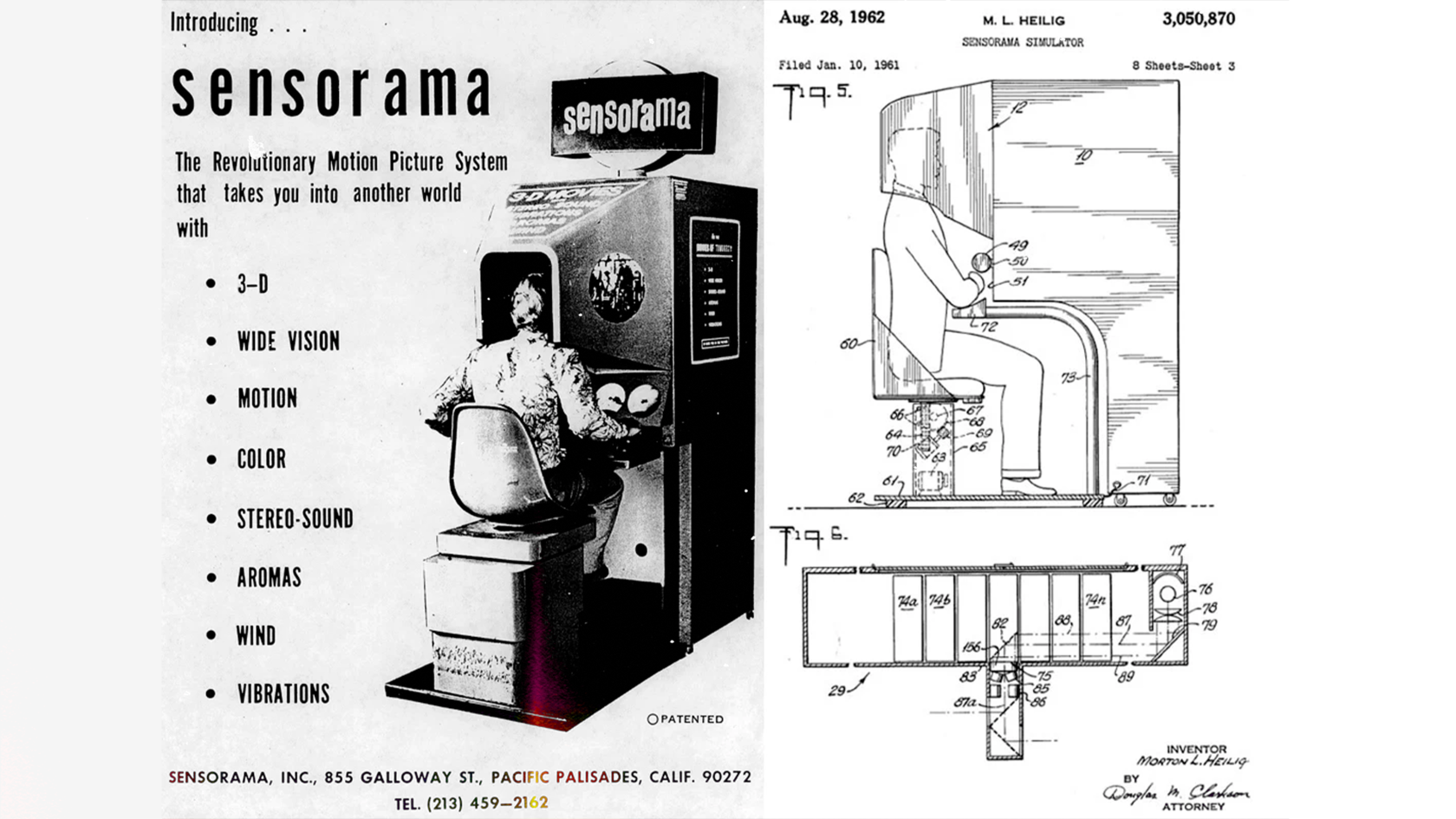

The first device that combined physical sensation and image simulation was Sensorama, the machine created by inventor and filmmaker Morton Heilig in 1957. Heilig's idea was to add touch, smell, and taste to image and sound to create a new art form that would be perceived in the same way as the real world is perceived by the human eye. To experience the new sensations, viewers would sit on a vibrating chair of a machine similar to an arcade game machine and place their heads in a special chamber. One of the short films made specifically for the device was a motorcycle ride through Brooklyn - thanks to built-in fans, an odor generator, and vibrations, the device gave a sense of immersion into what was happening. The environment created by the film still excluded the interactive interaction that today's VR helmets could provide. The technology was the first step towards simulating artificial environments, although Sensorama never gained mass popularity due to the high cost of production.

The idea of television goggles came closest to the look of modern VR devices. In 1961, two Philco engineers, Charles Comeau and James Bryan developed the Headsight device that became the prototype for today's virtual reality glasses. A separate video screen was created for each eye, with the ability to control an external video camera using head movements. It was not intended for entertainment but was developed for the intelligence services, but the principle of displaying an image on two screens for each eye formed the basis for further development of VR helmets.

In 1965, Ivan Sutherland described the concept of virtual reality as follows:

Three years later, he and students from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology designed The Sword of Damocles, actually one of the first AR/VR devices where the image was computer-generated. Sutherland's helmet was supported by a special metal lever fixed to the ceiling, and the technology itself allowed images to be altered by head movements, much like Google Cardboard does now.

The idea of television goggles came closest to the look of modern VR devices. In 1961, two Philco engineers, Charles Comeau and James Bryan developed the Headsight device that became the prototype for today's virtual reality glasses. A separate video screen was created for each eye, with the ability to control an external video camera using head movements. It was not intended for entertainment but was developed for the intelligence services, but the principle of displaying an image on two screens for each eye formed the basis for further development of VR helmets.

In 1965, Ivan Sutherland described the concept of virtual reality as follows:

- The virtual world is viewed through a head-mounted display (HMD) and appears realistic through augmented 3D sound and haptic feedback.

- Computer hardware is used to maintain virtual speech in real-time.

- Users interact with virtual objects in the real world.

Three years later, he and students from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology designed The Sword of Damocles, actually one of the first AR/VR devices where the image was computer-generated. Sutherland's helmet was supported by a special metal lever fixed to the ceiling, and the technology itself allowed images to be altered by head movements, much like Google Cardboard does now.

The first implementation of virtual reality is considered the Aspen Movie Map, which was developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1977. This computer program simulated a walk through the city of Aspen, Colorado, allowing you to choose between different ways of displaying the terrain. Summer and winter versions were based on real photographs - nowadays, similar technology with 360 degrees rotation is used to show products at conferences and exhibitions or, for example, in museums. In the mid-80s, there were systems in which the user could manipulate three-dimensional objects on the screen thanks to their response to the movements of the hand. NASA went a long way with this - the VR helmet VIEW[1] as an input device used the touch glove DataGlove, developed by VPL Research - a company founded by former Atari members Thomas Zimmerman and Jaron Lanier. In 1989, it was Lanier who coined the now-established term "virtual reality" that we still use today.

In the midst of the console wars, even before the release of its 64-bit system, Nintendo attempted to produce the first home game console capable of displaying "real" three-dimensional graphics. Although the final trend for this would begin with the first PlayStation, a feature of the 32-bit Virtual Boy was the ability to display 3D graphics in multiple shades of red and create a more accurate illusion of volume using the parallax effect. It worked like this: the player dipped his face into a pair of rubber shock absorbers at the front of the device, and two special projectors with LEDs in black and red transmitted the image separately for each eye. Sega, to its credit, had also made such an attempt two years earlier-the company announced its VR headset for the Genesis at the Consumer Electronics Show in 1993. The goggles tracked head movement and included stereo sound and an LCD display. However, the device remained only in the prototype stage. Sega justified the cancellation of the helmet by achieving an unprecedented level of realism, after which players could not be the same.

In the midst of the console wars, even before the release of its 64-bit system, Nintendo attempted to produce the first home game console capable of displaying "real" three-dimensional graphics. Although the final trend for this would begin with the first PlayStation, a feature of the 32-bit Virtual Boy was the ability to display 3D graphics in multiple shades of red and create a more accurate illusion of volume using the parallax effect. It worked like this: the player dipped his face into a pair of rubber shock absorbers at the front of the device, and two special projectors with LEDs in black and red transmitted the image separately for each eye. Sega, to its credit, had also made such an attempt two years earlier-the company announced its VR headset for the Genesis at the Consumer Electronics Show in 1993. The goggles tracked head movement and included stereo sound and an LCD display. However, the device remained only in the prototype stage. Sega justified the cancellation of the helmet by achieving an unprecedented level of realism, after which players could not be the same.

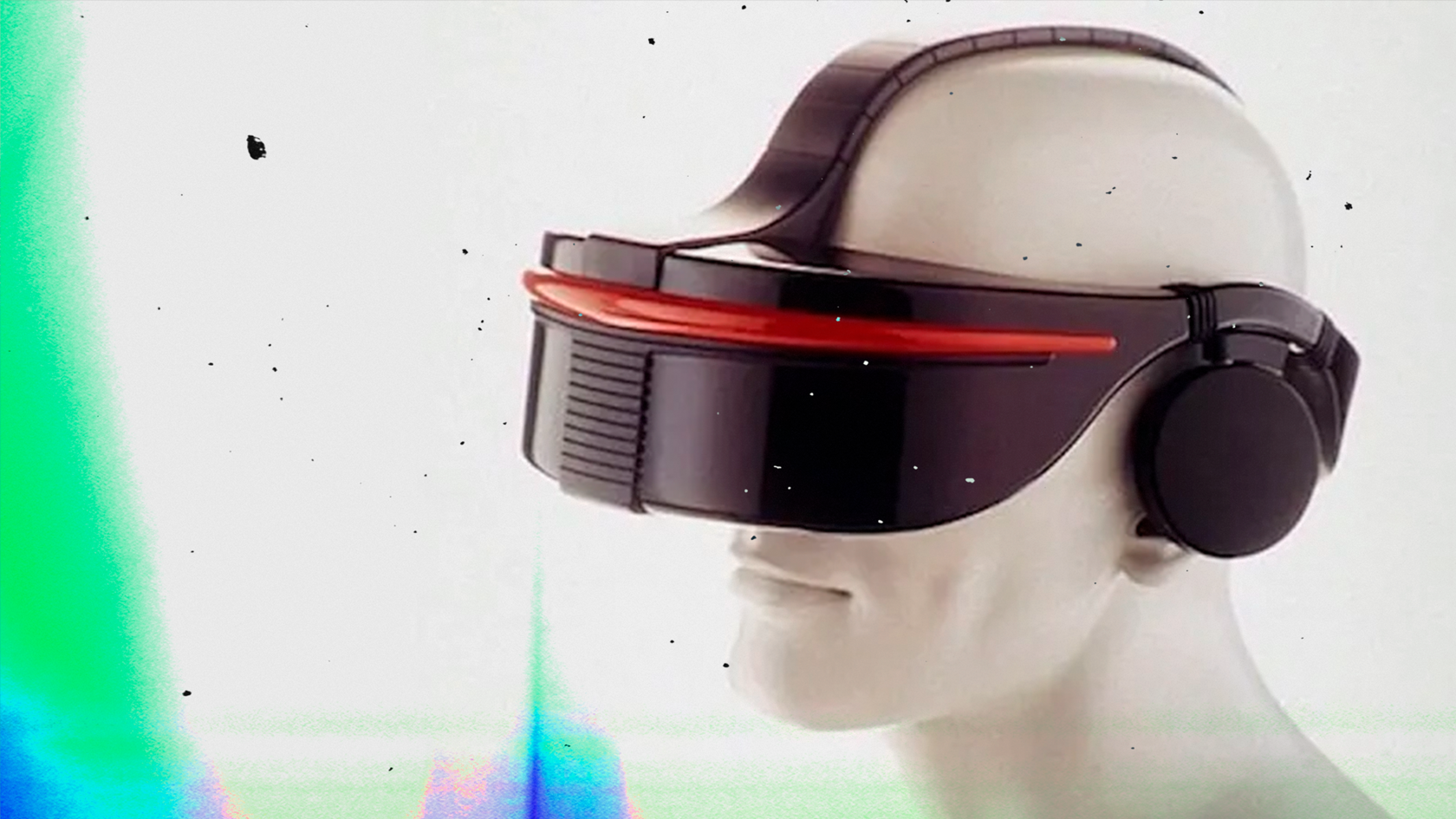

Sega's headset design ideas were inspired by the movies The Day the Earth Stood Still, Star Trek, and Robocop.

If Nintendo's device failed to conquer the mass market, attempts to create VR helmets didn't stop there. In the first half of the 90s, various companies tried to make their own devices, but all such developments either remained prototypes or were too expensive and complicated to set up. One such helmet was Forte's VFX1 from New York, which ran MS-DOS with games like Doom, Quake, Heretic, and Descent, which had a resolution of 263x230 pixels on both displays, a built-in gyro, and a magnetic earth field sensor but cost about a thousand dollars. Since then, there was a tangible breakthrough in the headsets of virtual reality, to be exact, with the development of Oculus Rift, which was announced in the 2012th. Then Palmer Luckey's team managed to raise almost two and a half million dollars on Kickstarter and received an investment of 91 million dollars while being bought out by Facebook for two billion dollars. It is interesting - later, the company's CTO was John Carmack, who worked on the very first Doom and, at the E3 2012, personally presented it during the announcement of the Doom 3 BFG Edition, compatible with virtual reality helmets.

The PlayStation VR headset.

In fact, the virtual reality market, as a phenomenon, at least somewhat formed, is only a few years old as of 2021. It is still niche, and of the main games we can highlight only a few - Beat Saber, where you have to smash cubes to a musical beat by analogy with Guitar Hero - it has over a million sales (Facebook also bought it), survival-horror Resident Evil VII, which although has VR-mode, but perfectly able to work without it, and Half-Life: Alyx - continuation of the Half-Life series, which could raise sales of Valve Index headset, make a splash, but not to the point of global changes in the market. So far, the most popular and affordable VR headset in the consumer segment is the PSVR. Thanks to the PlayStation's large install base[2] and relatively affordable price conditions, more than 5 million devices have been sold as of 2020, and the company promises to release a second version by the end of 2022.

Nevertheless, analysts are talking about big growth for the foreseeable future, though they predict it at the turn of the next ten years. By 2025, spending on VR content alone will exceed $4 billion, but VR is likely to become truly mainstream closer to the beginning of 2030. About 6.4 million VR headsets were sold in 2020, with 3.3 million of those being standalone headsets. Revenue from the sale of VR-content by the end of 2020 is about 1.1 billion dollars, and the total turnover of the segment is almost 16 billion, while the total revenue of the virtual reality market in 2025, should be about 10 billion dollars, of which 4 should come to VR-content, and the vast majority of it is for games, and by 2028 the forecast approximate income is estimated to almost 70 billion dollars. Apple, too, is not going to stay away and is planning to release its first VR headset in 2022.

Nevertheless, analysts are talking about big growth for the foreseeable future, though they predict it at the turn of the next ten years. By 2025, spending on VR content alone will exceed $4 billion, but VR is likely to become truly mainstream closer to the beginning of 2030. About 6.4 million VR headsets were sold in 2020, with 3.3 million of those being standalone headsets. Revenue from the sale of VR-content by the end of 2020 is about 1.1 billion dollars, and the total turnover of the segment is almost 16 billion, while the total revenue of the virtual reality market in 2025, should be about 10 billion dollars, of which 4 should come to VR-content, and the vast majority of it is for games, and by 2028 the forecast approximate income is estimated to almost 70 billion dollars. Apple, too, is not going to stay away and is planning to release its first VR headset in 2022.

Oculus Quest 2.

In general, the future of VR is clear, and we will be able to catch the dawn of this technology, but we will have to wait until this technology becomes mass and work as Netflix on one button. VR headsets are gradually getting rid of wires, like the same Oculus Quest or Oculus Go, but they do not yet have enough "guts" to equal the stationary solutions used in conjunction with the PC. The only option that could come closest to solving the above problems as of 2021 is the Oculus Quest 2, which has beaten the wires and managed to lighten the weight of the design. So far, it's looking like both problems will be solved as the technology develops, and we'll see our Sword Art Online yet. Augmented reality is also not standing still, but so far, AR-solutions are finding themselves more in other areas than in the games. To become really popular, at the moment, could only Pokemon GO, where it was mainly the specifics of the franchise and, so far, it is used mostly in conjunction with mobile devices. There is a high probability that augmented reality will be part of future VR headsets, which will become hybrid solutions and, conventionally, have two modes - one allowing to use the usual everyday functionality, and the second to be used for full immersion.

Cloud gaming: video games of the future

Gamepads and phones, too, were gradually getting rid of unnecessary wires so that their modern ergonomics could become the most comfortable for everyday use. VR is moving along this path as well, but... What if we get rid not just of wires but of the system unit altogether? What if we only had a monitor, the ability to transfer information from interactive input devices over a network, and the result could be played back using streaming? What ten years ago would have sounded like science fiction, today is a full-fledged trend that can turn the video game industry in the near future and make a technological revolution in it. Cloud gaming - it is the ability to play on everything, having only an Internet connection and a device that can display the picture and send user commands to a remote server.

The OnLive service worked perfectly on tablets and smartphones, allowing you to run the top games of it time.

The statement that it was a fantasy ten years ago is only half true - a solution for the mass market appeared in 2010 and worked surprisingly well. The OnLive service developed dynamically and received over $50 million in investments, and at the peak of its development, its audience reached 2.5 million users. In parallel with OnLive, a similar service Gaikai was developing, which in 2012 was bought out by Sony for $380 million, later becoming part of PlayStation Now, as well as OnLive in 2015. The service went from beta testing to public release on January 13, 2015. Since that time, the service switched to a subscription model, although previously users had to pay for each game. At the end of 2019, the cost of a monthly subscription in the U.S. came to a price tag of $9.99, and the service's library contains about 800 games from past years from PlayStation 2, PlayStation 3, and PlayStation 4 consoles. Kind of reminds you of Game Pass from Xbox, doesn't it? Since the subscription system was able to become popular in the movie industry, what's to stop it from being moved to the rails of the video game industry?

By 2020, cloud gaming has managed to become a full-fledged trend - giants like Tencent, Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Nvidia, or Beeline, Sber, and Mail.ru when it comes to the Russian market, are now entering this paradigm. The average price to get access to a subscription for unlimited play is about 1,000 thousand rubles, and services are moving to a model that involves not paying for each individual game, as was the case with the service GFN.ru, for example. The latter, by the way, reached the mark of 135 thousand users in 2020 because of restrictions associated with the COVID-19 global pandemic.

By 2020, cloud gaming has managed to become a full-fledged trend - giants like Tencent, Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Nvidia, or Beeline, Sber, and Mail.ru when it comes to the Russian market, are now entering this paradigm. The average price to get access to a subscription for unlimited play is about 1,000 thousand rubles, and services are moving to a model that involves not paying for each individual game, as was the case with the service GFN.ru, for example. The latter, by the way, reached the mark of 135 thousand users in 2020 because of restrictions associated with the COVID-19 global pandemic.

The GFN.ru service, like OnLive in its time, is positioned as an opportunity to play from any device.

The Russian government also pays a lot of attention to the technology and intends to increase the export volume of cloud gaming services by 55 times by 2030, rising from $2.9 million in 2020 to $160 million, while the service audience is expected to grow from 180 thousand to 10 million people.

As for the dramatic changes for the industry that the system itself can bring in the near future - several areas have the chance to have a significant impact:

A new level of design is something that, in theory, allows you to realize computing power that you can't get on an ordinary home PC. To ray tracing in real-time, which could only be seen in 3D cartoons, could at least somehow get closer only with the release of the latest generation of graphics cards and the last generation of home consoles. In order to "juice up" the maximum number of objects on the screen, effects, reflections, and all sorts of calculations for this feast of visualization, you need to upgrade your home PC every few years. Subscribing to a cloud service makes it easier for the end-user, who stops worrying about such things from now on, and the company, in turn, gets to offer a unique experience that, in principle, is virtually unattainable at home. Such a change could lead to complex physical models in video games and sophisticated simulations, the ability to create entire worlds without any extra loading, and give players a completely different experience, like eSports in Ender's Game movie.

As for the dramatic changes for the industry that the system itself can bring in the near future - several areas have the chance to have a significant impact:

- The mobile gaming market

- A new level of quality for video games

- Multiplayer gaming.

A new level of design is something that, in theory, allows you to realize computing power that you can't get on an ordinary home PC. To ray tracing in real-time, which could only be seen in 3D cartoons, could at least somehow get closer only with the release of the latest generation of graphics cards and the last generation of home consoles. In order to "juice up" the maximum number of objects on the screen, effects, reflections, and all sorts of calculations for this feast of visualization, you need to upgrade your home PC every few years. Subscribing to a cloud service makes it easier for the end-user, who stops worrying about such things from now on, and the company, in turn, gets to offer a unique experience that, in principle, is virtually unattainable at home. Such a change could lead to complex physical models in video games and sophisticated simulations, the ability to create entire worlds without any extra loading, and give players a completely different experience, like eSports in Ender's Game movie.

In Ender's Game movie, the main character's training was based, among other things, on a game that used simulation in the absence of gravity.

Just such tricks involve the latest trend, multiplayer games. To get closer to those conditional movies and their setting that were mentioned in the beginning - you need to have everything built on the server-side at all. To put it simply: all major MMOs now work in such a way that the game is installed on the user's system, and the calculation of interactions with other users takes place on the server. All the graphics - models, animations, the display of another user is done by the home PC, which receives only the digital data, which is already processed by the server. That would be OK, but displaying a few thousand users and their actions at once is not an easy task for a home PC. So, in the case described above - everything will be on the server-side, whose processing power is limited only by the capabilities of its owners. This means that the hypothetical Ready Player One takes place exactly on such a server, and the player himself only needs to put on his glasses and turn on his virtual reality device, as it was shown in the movie. By the way, getting back to its topic - to come close to such an effect, you need a high-speed Internet connection. Since the days of Virtual Boy, although much has changed, but the picture is still fed to each eye separately - it is already twice as much information, not one computer screen, besides the need for high resolution and frame rate of 120 FPS - another convention for VR, which is necessary for a comfortable game.

Neural Networks and Neural Interfaces

As of 2021, we have tools that allow us to develop games using only visual scripting and writing logic - everything is moving towards making games even easier. Neural networks and BigData will gradually take over even more processes, leaving more room for the most daring ideas, like NVIDIA's GameGAN neural network recreating Pac-Man in four days in 2020. Before becoming game creators, neural networks also managed to become odious opponents - just a year earlier AlphaStar from DeepMind was able to win on the professional stage in Dota 2 and Starcraft II, moreover, it had previously succeeded in such games as Pong, Breakout, Space Invaders, Seaquest, Beam Rider, Mario, Quake III Arena in CTF mode.

The Matrix is an iconic late-'90s film about virtual reality simulation.

The real world will seem flat, colorless, blurry compared to the experiences you'll be able to create in people's brains," Gabe Newell says in an interview on New Zealand's 1 News, referring to neural interfaces. According to him, Valve is interested in the possibility of connecting the brain directly to the computer and already has its own developments, in particular, an open-source program that could become a bridge between developers and brain signals. The new experience Newell is talking about is already much closer to a notional The Matrix or "Deeptown" from Sergei Lukyanenko's "Labyrinth of Reflections" trilogy - in theory, the ability to interact with the virtual world and the instant response that can take eSports to a whole other level. In the second episode of the third season of the Black Mirror series the plot is based on the interaction of a video game tester with the virtual reality, which adjusts to his fears - with neurointerfaces such mechanics, and, for example, dynamic complexity, may well be implemented.

Throughout history, whether it was the era of the arcade game machines, the console wars, the emergence of new genres, handheld devices, the possibility of online gaming, virtual reality, or the advent of leaving only monitors and gamepads, abandoning the system, history has always moved to where it can offer the player a unique experience. Whichever way you look at video games, whether they are mass-market entertainment or art, video games have something that no other industry can offer, namely interactive interaction... The ability to operate in schemes, conditions, and paradigms that are limited only by the intention of their creators. If our world has laws that are formed and understood by us, then for video games, these frameworks can be expanded, and the laws by which it will operate can be subject to change.

VR and AR are already actively used within the B2B-segment, education, simulations to work in dangerous situations for humans, control of robotics and drones, but its origins are, to a great extent, taken from the video game industry. We cannot know what will happen in the future with 100% probability, but the road that leads to it is already taking shape, and it is not made of yellow bricks but of numbers that can add up to something incredible.

VR and AR are already actively used within the B2B-segment, education, simulations to work in dangerous situations for humans, control of robotics and drones, but its origins are, to a great extent, taken from the video game industry. We cannot know what will happen in the future with 100% probability, but the road that leads to it is already taking shape, and it is not made of yellow bricks but of numbers that can add up to something incredible.